A great teacher will leave behind a raft of students doing well.

That’s how I first heard of Ernie Johnson.

That’s how I first heard of Ernie Johnson.

As I moved back to Southern California and began writing about the area, I ran into his students, now well on in life and doing very well. The name came up a few times.

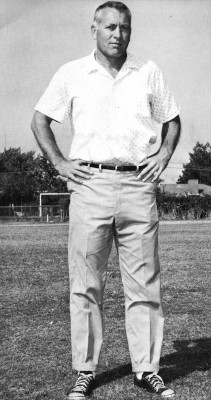

Johnson was a legendary football coach, producing dominant teams at El Rancho High School in Pico Rivera and later at Cerritos College.

He was one of the first coaches to meld white and Hispanic players into football dynasties — a rare thing back then.

Johnson died last month at the age of 87.

He was one of those Marine-style football coaches, who took kids by the face mask to make a point.

The first to tell me of Johnson was Ruben Quintero, who played offensive tackle on the great El Rancho teams in the mid-1960s. Quintero is a professor of literature at Cal State, Los Angeles.

(I met Quintero while doing a story in 2007 on the murder of his sister, Maria Hicks, who had accosted some taggers writing on a wall and who fired upon her when she approached.)

In the mid-1960s, El Rancho High School had just been formed from parts of two school districts, after Whittier wanted to rid itself of a chunk of its district that had a lot of Mexican-Americans. On one side of the new district lived working-class Mexican-American; on the other, middle-class whites.

Johnson forged them into a statewide football force. El Rancho crushed its opponents during these years. It was chosen the nation’s best football team one year.

“He had a very successful football program at same time that the city was working to unify north and south parts into one program,” Quintero told me. “We were all part of something that in many ways representative of what Pico Rivera was, a kind of mixed community that was doing something very, very successfully. We were a public school that beat all these Catholic schools that could recruit from all over the place.

“He crystallized in the successful football program something that was larger in the community.”

Johnson didn’t allow dancing celebrations or steroids or trash talking. But the El Rancho squad was so dominant that the players would go three quarters, take no water, never take off their helmets and begin doing jumping jacks as the the fourth quarter started to cow their opponents. That’s what Quintero told me.

A couple years later, I met Ernie Vargas, the recreation director for the city of Hawaiian Gardens, on a story I was doing about his use of rugby as way of guiding kids away from gangs. Vargas played for Johnson at Cerritos College.

Vargas lacked football talent, but had a desire to play that impressed Johnson.

“In the neighborhood, a lot of kids didn’t have discipline,” said Vargas. “Not only was I being coached, but I was also being mentored to be a better man. These were the principles I live by today. I don’t need to steal. I don’t need to lie. Be true to myself. Coach wanted us to be true to ourselves. I was just in awe of what he had to say.

“He said: Be where you’re supposed to be. Be on time. And do your best. Those three principles are all you need for life.”

(YOUR OWN MEMORIES OF ERNIE JOHNSON? Please add them to Comments below.)

I later interviewed Johnson, the son of Texas cotton pickers who had came to Orange County to pick citrus, by phone. Here are a few things he said:

–“It’s like playing human chess, football is.”

-“El Rancho High School was built to cleanse Whittier High School of Mexicans. We got every gang – Jimtown, Canta Rana from Los Nietos. What they didn’t understand was that they also got rid of a lot of great players and all the good-looking girls.”

-“I was raised in a Mexican neighborhood in Fullerton. They called me Gringo Uno. I learned more in the neighborhood that eventually helped me because they couldn’t tell me about being poor. Having been raised where I was, I was a minority for a long time myself. The people in Fullerton honestly thought that I was an albino because they never saw me with anyone but Kiko Munoz and Eddie Montoya.

that eventually helped me because they couldn’t tell me about being poor. Having been raised where I was, I was a minority for a long time myself. The people in Fullerton honestly thought that I was an albino because they never saw me with anyone but Kiko Munoz and Eddie Montoya.

-“At a reunion not long ago, two guys came up and said., `You don’t know who we are. I’m Naranjo from Jimtown. The other was Ray Chavez from the Montebello Jardines. I had them both in continuation PE. I would tell them,`You change your ways or you’re going to die in the gas chamber.’ They said, `We came here to tell you we did not die in the gas chamber.'”

-“One night we beat Whittier, the team all knelt and prayed. We always sprayed before the game but never prayed to win. We prayed that nobody got hurt, and have the privilege of playing. Then we get a complaint from Whittier about us praying on the field. I said I didn’t tell them to get down and pray and I’m not going to tell them to get up. Then they saw what miserable little people they were.”

And my favorite:

-“If there’s one secret to being a coach, it’d be to show you love your players more than you love the game.”

Two memorials for Ernie Johnson are planned.

One is a tribute at halftime of El Rancho High School’s football game on Friday night, November 1.

The next is a memorial service Sunday, November 3, 1 p.m. at the high school, 6501 Passons Blvd., in Pico Rivera.