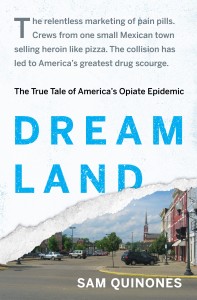

This fall I traveled a lot to Heartland areas to talk about a book I’d written about opiate addiction in America, and this provided me with a close view of the rise of Donald Trump’s candidacy.

The areas where I spoke were particularly hard hit by narcotic abuse — rural Michigan, southern Indiana, West Virginia, Kentucky, and several towns in rural Ohio.

The prevalence of Trump/Pence yard signs in these areas, particularly by mid-October, was stunning. As I traveled, it seemed palpable, this connection between Trump support and opiate addiction.

Not that there weren’t other reasons people supported him. A suffocating political correctness on the left is another factor in his appeal, I believe.

But nothing darkens your view of your present and future prospects quite as thoroughly as addiction to opiates (pills or heroin) in your family, on your street, or in your town. With opiates comes a fatalism and negativity that clouds a town or a family’s feeling about its world, even as unemployment falls and the economy improves.

In theory, addiction knows no race. In reality, though, our national opiate scourge is almost entirely white. Very few non-whites are among the newly addicted to prescription pain pills, then heroin. In three years of book research, I met one.

Though this scourge has affected every region of the country, it is felt most intensely in rural, suburban – Heartland – areas of America where Donald Trump did extraordinarily well.

Some of these areas did not fully rebound from the Great Recession of 2007 (southern Ohio). Others fared much better (North Carolina). A common denominator, I think political scientists will find, is that in these areas since the last presidential election the incidence of opiate addiction spread, grew deadlier, more public, and went from pain pills to heroin. In southern Ohio, where heroin has hit like pestilence, particularly Appalachia, Trump trounced his opponent in counties that Mitt Romney barely won four years earlier – though unemployment in many of these counties is at its lowest level in years, sometimes decades.

Shannon Monnat, a rural sociologist and demographer at Penn State I talked with, found strong correlations between suicides and fatal drug overdoses in counties where Trump’s increase was larger that the share of the vote compared to Romney’s four years earlier – this in six Rust Belt states, another half-dozen state in New England and all or part of the eight states comprising Appalachia.

One place I spoke was Hocking County (pop. 28,000). Hocking has lost coal mining jobs in recent years, though its unemployment rate dropped this fall to 4.5 percent, the lowest in more than 20 years. (It hit 14 percent in 2010.) But Hocking has also grown far more aware of its pill/heroin problem. Overdose deaths are up. Its drug court is among the first in the state to use Vivitrol, the opiate blocker. Trump earned 66 percent of the vote in the county Romney carried with 49 percent four years ago.

Opiate addiction – to pain pills or heroin — is the closest thing to enslavement that we have in America today. It is brain-changing, relentless, and unmercifully hard to kick. Children who complain at the slightest household chore while sober will, once addicted, march like zombies through the snow for miles, endure any hardship or humiliation, for more dope.

In many of these regions, folks were unprepared for it and, what’s more, believed they had done nothing to deserve it. Kids with no criminal record, star athletes, pastors’, cops’, and mayors’ kids all got addicted. Parents who’d imagined some glowing life script for their newborns years before were, as those kids reached young adulthood, confronted instead by late-night collect calls from jail, lying, stealing, conniving and that child’s body seemingly occupied by a mutant beast. Then came a felony record. Suddenly parents were co-signing for apartments, providing money and transportation for their addicted beloved, now 24, to take a GED class.

Though the number of actual addicts is small, the epidemic’s political impact has been substantial.

First because the states where the epidemic is most intense were crucial to the victor – whoever it was going to be.

Also, though, the opiate addiction rippled far beyond each individual addict. Addiction colored the lives of siblings, grandparents, uncles and aunts, friends and neighbors, pastors, teachers. As parents lost their fear of speaking out in the last two years, the problem emerged from the shadows, media coverage expanded, and now everyone for miles around was aware of it. County budgets buckled. Merchants saw theft increasing.

In several counties I visited, employers reported that more than half their job applicants couldn’t pass a drug screen. So though unemployment numbers fell, a good chunk of that was because many people were too hooked to seek work. Imagine what that does to a county’s productivity, and its buoyancy of spirit. It explains how a declining unemployment rate could create not optimism, but the foreboding that seemed to motivate many voters.

People also grew to understand that virtually all our heroin comes from or through Mexico – which is why it is cheaper and more potent than ever in our history. That did nothing to engender love for our southern neighbor in regions that had lost factories as well as kids. Nor did it make them feel that we have a serious and modern partner in Mexico when it comes to criminal justice and law enforcement.

This story plays out today with intensity in several of the states crucial to Trump’s victory – Ohio, North Carolina, Pennsylvania. It does the same in states he was assumed to win: West Virginia, Oklahoma, Utah, Kentucky, Indiana, Alabama, Georgia, Tennessee, and others. That these states – largely rural, religious, and white – are now our heroin beltways amounts to a stunning change in our national culture and one that most people in those areas became aware of only recently.

Equally stunning is that New York, California and Illinois – including New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago, once our heroin hotspots – are well down the list of states ranked by addiction rates. Hillary Clinton won each of them.

In many of the most affected regions, moreover, people, by and large, have taken as self-evident Ronald Reagan’s dictum that “government is the problem” — the starkest threat to personal freedom. The private sector and the free market are, therefore, to be exalted; government starved. (This despite a deep reliance on government programs: Medicaid, Medicare, SSI, SSDI, worker’s compensation, food stamps, welfare, farm subsidies, etc.) Confederate flags and 2nd Amendment bumper stickers were common amid the Trump signs I saw.

The irony is that behind this drug plague is a story of how the private sector introduced the most serious widespread threat to personal freedom in America today – opiate addiction. All profits from the massive prescribing of narcotic pain pills have accrued to the private sector, mainly pharmaceutical companies; all costs of addiction to those pills, and then heroin, are borne by  the public sector. Indeed, for years, about the only people fighting the opiate scourge, my research showed, were government employees: cops and prosecutors, public health nurses and CDC statisticians, county social workers, judges and ER doctors, DEA agents, coroners and others.

the public sector. Indeed, for years, about the only people fighting the opiate scourge, my research showed, were government employees: cops and prosecutors, public health nurses and CDC statisticians, county social workers, judges and ER doctors, DEA agents, coroners and others.

The Sackler family, which owns Purdue Pharma, the company that makes OxyContin, has been estimated by Forbes magazine to be now one of the country’s wealthiest, with an estimated net worth of $14 billion, due to $35 billion in sales of the drug since it was released in 1996.

All this, I believe, helps explain the reception to Donald Trump’s populist message – including rejection of free trade and other sacred cows of Republican elites and conservative theorists. (“Worst Election Ever” proclaimed a post-election article from the conservative Hoover Institution.)

In these areas, too, the “throw away the key” approach to drug addiction was unquestioned dogma until the opiate scourge. That is changing. Democrats may still not get elected in a region like northern Kentucky, for instance, but Republicans who talk only tough on crime now have a hard time there, too – so harsh is the pill and heroin problem.

It’s likely that many of the regions where Trump enjoyed such support will require massive investment in drug treatment before they can be great again. (Ohio Gov. John Kasich realized that and went around his Republican-led state legislature a couple years ago to mandate Medicaid coverage for all Ohioans — largely because it gave people coverage for drug treatment.)

Will such an investment come from a president whose election seems to have so much to do with the opiate epidemic, yet who appears to have thought little about how to expand drug treatment?

How will people in these areas react to dismantling Obamacare, which provides coverage for addiction treatment that they didn’t have before?

In counties where half of job applicants fail drug screens, will the chambers of commerce line up to do away with the system?

Like so much that sprang from those Heartland yard signs, I guess we’ll see.