There’s been a dust-up recently over a meeting that LAPD investigators held with Rene “Boxer” Enriquez, a former influential member of the Mexican Mafia prison gang, in which he explained to them the inner workings of his former crime pals.

The mayor is criticizing the meeting, questioning why it was held. LAPD Chief Charlie Beck has called for a review of the decision to hold it. LA Police Commission President Steve Soboroff has called for an investigation into the meeting. Soboroff called the meeting a “giant waste of resources” and “very very misconceived.”

LA Police Commission President Steve Soboroff has called for an investigation into the meeting. Soboroff called the meeting a “giant waste of resources” and “very very misconceived.”

I don’t know what happened at that meeting, but if it was anything like the kind of law-enforcement seminar Enriquez has given dozens of times in the past, then Soboroff need to reassess that opinion.

What is the problem here?

Why would you not want a former Mexican Mafia member to be educating police brass on the workings of one of the most influential, and little-known, institutions in Southern California life today?

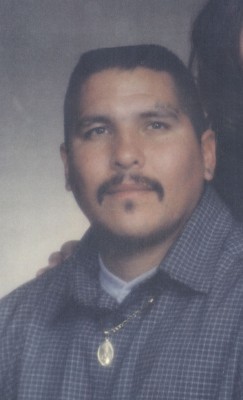

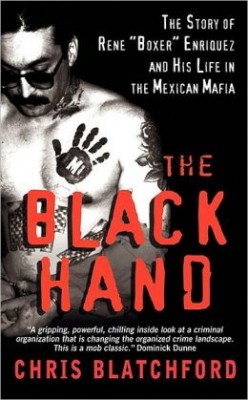

Boxer has made a second career (behind bars – he’s serving life in prison) of teaching law enforcement about how his old mates work. I’ve interviewed him extensively. That’s what he does, and, an articulate fellow, he does it pretty well. (He’s co-author, with local TV reporter Chris Blatchford, of the book, The Black Hand, released in 2009.)

Far from being a “giant waste,” this seems to me to be essential work. The Mexican Mafia is one of the most important institutions in Southern California, particularly in communities with large Latino populations and gang problems.

The Eme used to be just a prison gang. But two decades ago, it marshaled the forces of street gang members to tax drug dealers in their areas, and sometimes also fruit vendors, bars, prostitutes and others – and funnel the proceeds to Eme members, their families and associates.

With that, it became Southern California’s first regional organized crime syndicate.

It’s probably less than that description implies, as it’s run by drug addicts locked away in maximum security prisons, who use drug addicts and criminals as their go-betweens. The miscommunication can be monumental. Still, the mafia has changed life in many parts of this region.

In some SoCal towns, its members are more important than the mayor, with enormous impact on town budgets. Its members can create – have created – crime waves with simple orders to associates who pass them along to gangsters on the street. The Eme has been shown to have alliances with Mexican cartels.

Sounds to me like anyone willing shed light on an organization like that ought to be welcome.

By the way, I contend that Enriquez’s decision to drop out while he was in solitary confinement in Pelican Bay in 2001 was a crucial moment in state prison history, as it helped pave the way for the mass defection of gang members in prison.

It wasn’t the only factor pushing that along, but it was important because it showed the Eme’s soldiers and lieutenants that their higher-ups weren’t going stick with the program. Also, two other mafia members – Angel “Stump” Valencia and David “Chino” Delgadillo – quickly followed him into PC, with several others after that, including Boxer’s old Eme buddy, Jacko Padilla, who controlled the Azusa area.

Protective custody in state prison went from a few hundred to, today, tens of thousands of inmates on what are known euphemistically as Sensitive Needs Yards. Many of them are Southern California Latino gang members. All that picked up enormous momentum after Enriquez dropped out.