Last night, in the middle of a 90-minute set in West L.A., Alejandro Escovedo hunched over his black electric guitar and splayed his feet as if he was up against gale-force winds.

Last night, in the middle of a 90-minute set in West L.A., Alejandro Escovedo hunched over his black electric guitar and splayed his feet as if he was up against gale-force winds.

He leaned into his lead guitarist and a schoolboy grin spread across his face.

I think the song was Neil Young’s “Like A Hurricane.” But I can’t remember any more.

All I remember was the pure exhilaration on his face, which I took to mean that he still sucks a ton of joy from the simple act of playing in a band and getting it to thunder like a herd of African wildlife.

I took my wife to see Escovedo at The Mint on Pico Boulevard (great place!).

He was backed by the Sensitive Boys. This was a real garage band – which is all any rock musician with any balls should aspire to. I mean, the drummer had only four drums. (Thanks, man!) The guitarist had two guitars. Same with Escovedo. The bassist – bless his heart — had only a four-string Fender.

The gear didn’t matter. What mattered was the spirit. The idea that all you needed was your own heart, and jagged point of view, and love of fun.

Escovedo knows how to choose a great cover (“All the Young Dudes”), but he’s not an oldies act. Just a survivor.

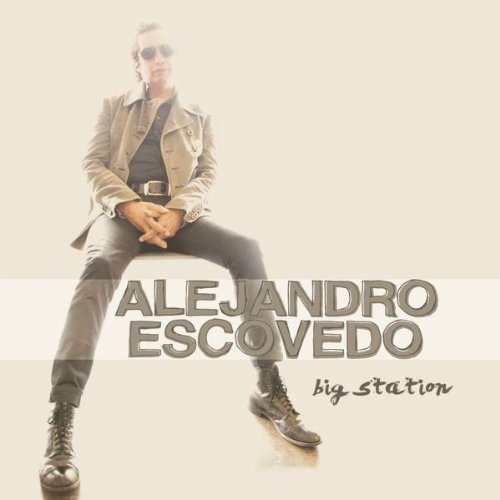

He made his life in a young man’s game and, more than 30 years later, continues to create within it. He’s got a bunch of albums of his own songwriting.

Escovedo is one of the few from the original wave of punk rock (1977-81) who’s still making music. He was in the SF punk band, the Nuns, then Rank n File. Moved to Austin. I think since the late 1980s he’s been crafting his own career as a singer-songwriter who plays acoustic guitar but whose big love is for a nasty old pawn-shop electric turned up loud.

All I know is that mostly folks who started out with him are all dead or gone on to other things. Or they’re in the RocknRoll Hall of Fame, which amounts to the same thing.

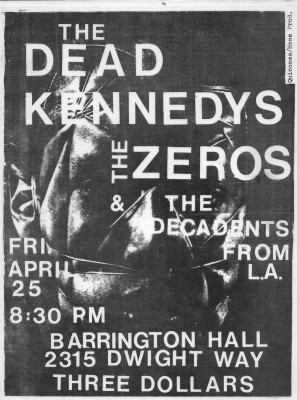

Punk rock was a joyous moment, an essentially American thing. It told a bunch of kids who grew up on a rock music that was now fat and pompous: You know what? Screw Emerson Lake and Palmer.

You don’t need stacks of amps and $5000 guitars and walls of drums. Screw the elites. You can get up there and do it, too, if you have the spunk.

Hell, you don’t even need to know how to play.

And you damn sure don’t need one of those pretentious six-string bass guitars.

All you need is three chords and the hunch that you need to make life on your own terms. Record your own 45s, book your own gigs, print your own posters. Everything’s up to you. Just don’t ask permission.

That is healthy stuff for a kid to hear. It was for me. It changed my life, though I was never in a punk band. (I did promote my own punk shows, though. Even hired the Zeros, fronted by his brother, Javier, a time or two.)

Any pop music genre is born in times and circumstances and doesn’t easily survive their passing. Punk was no different. It died long ago. The blues died, too — years ago. People can still play it. They still play Dixieland in New Orleans. Doesn’t mean it’s vital any more.

But if it’s worth anything, that music will leave a residue of attitudes that helped create it.

Like gum stuck on a shoe, one piece of punk’s residue is Alejandro Escovedo. Now with “more miles than money,” to quote his lyric, the independence of his spirit doesn’t seem to have flagged much.

Last year’s “Man of the World” is the best straight-ahead, raspy garage rock song in years.

Last night, his “Rosalie” hit me as one of the purest love songs I’ve heard in a while. I’d heard it before, but not live, which helped, though I can’t say why. Maybe it was just more raw, like the feeling. It’s a true story of a boy from San Diego and a gi rl from El Paso who met one day, fell in love, and spent the next seven years writing letters to each other until they saw each other again.

rl from El Paso who met one day, fell in love, and spent the next seven years writing letters to each other until they saw each other again.

He filled the spaces between songs with stories of his family – parents and their 12 kids – coming out to Huntington Beach from San Antonio for vacation, seeing the beach and literally never going back, and of years later waiting outside the Whiskey to see the New York Dolls.

Then he sang another love song: “Sweet Jane” – it was to Lou Reed. “Sing it for Lou” he yelled, as the four chords to the song churned on and on through the night.

We did.