As a reporter, I don’t believe too much in coincidences, especially when it comes to Mexican politics.

As a reporter, I don’t believe too much in coincidences, especially when it comes to Mexican politics.

So, let’s say that the arrest this morning of drug megalord Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, coming just as Mexican President Enrique Pena Nieto is featured on the cover of Time Magazine, with the headline, Saving Mexico is, well … let’s say, it’s interesting.

The man flaunted his impunity and could, presumably, have been arrested many times — say, during his well-known marriage to a young girl in the mountains of Durango several years ago.

Guzman’s no dummy and he probably should have been ducking when he heard of the Time cover, which is rare territory for a Mexican president. Instead Guzman was at a condo complex in Mazatlan, my favorite Mexican resort town, as it prepares for its nationally famous Carnival, which tens of thousands of people attend. He was captured without a shot fired by the Mexican Navy, which is quickly becoming the country’s leading law enforcement agency, having also taken down Arturo Beltran Leyva, among others.

(According to the Mexico Attorney General, Jesus Murillo Karam, Guzman used tunnels and even city drainage pipes to get around Mazatlan. Here, btw, is the press conference, which ends with them walking him before reports to a waiting helicopter.)

Pena Nieto has been roundly criticized for the way he’s waging the drug war. So Guzman’s arrest allows him to seriously recover his image, just as this cover hits the stands.

In the past, each Mexican president was supposed to get one kingpin to take down. Carlos Salinas had Joaquin Hernandez, aka La Quina, the oil union boss. Ernesto Zedillo had Juan Garcia Abrego, of the Gulf Cartel, though he tacked on Salinas’s brother, Raul, for good measure.

Vicente Fox broke with tradition and had Osiel Cardenas Guillen and the top Arellano Felix brothers. Felipe Calderon, who spent his sexenio mired in this awful war, took down numerous, including Los Zeta’s Heriberto Lazcano.

We’ll see how many more EPN has in him. After all, the Sinaloa Cartel still has Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada — who is Guzman’s partner and co-equal atop the organization.

Meanwhile, we’ll expect Guzman to remain locked up this time, and not escape as he did in 2001. Look, also, for him to be extradited quickly to the US, where he faces several major federal indictments for trafficking. (The DEA in Chicago is already saying they want him in court in that city.)

Cynicism aside, though, the arrest of the man Forbes once listed as one of the world’s wealthiest men is only to be applauded. It’s very much like the moment when Obama took out Osama bin-Laden.

Mostly, his arrest goes some distance to showing that the old idea of criminals protected by the regime is passing, however slowly, from Mexican political culture. Next up — a few governors, perhaps?

Mostly, his arrest goes some distance to showing that the old idea of criminals protected by the regime is passing, however slowly, from Mexican political culture. Next up — a few governors, perhaps?

In fact, it opens the question of what comes next. More violence? Very possible, as groups regroup and fight for territories that were once settled issues. After all, this war really dates to the moment Osiel Cardenas Guillen was captured in 2003 and Chapo figured that was a good time to go after Gulf Cartel territory that he thought was vulnerable — incorrectly as it turned out.

Chapo’s story is an amazing one, as is the story of all the Sinaloan narcos. He, and most of the rest, grew from the Sinaloan mountains and, especially, the county of Badiraguato, hillbilly kids who rose to control the drug flow through the key points — known as plazas — along some 1400 miles of the 1900-miles border between Mexico and the United States. Sinaloans formed no fewer than three major drug cartels — and they feuded mightily through the years.

I’ve always thought it was one of the remarkable tales in the history of organized crime anywhere.

Some may say that Guzman will only be replaced by another. That’s possible.

Some may say that Guzman will only be replaced by another. That’s possible.

Still, I’ve become a believer in the idea of taking out mafia kingpins.

They’re usually kingpins for a reason. They have remarkable organizational talents, great at logistics, and usually combine all that with a psychopathic taste for blood. Managing to smuggle tons of drugs across a well-guarded border using criminals and gang members is a real talent that I suspect few people truly possess. They’re not easily replaced.

I once interviewed a trafficker from Tijuana’s Arellano-Felix cartel. He said the beginning of the end for that now-fractured group came with the arrest of Ismael and Gilberto Higuera, who ran Tijuana and Mexicali for the brothers. The Higueras were experts at logistics, organization, and murder, he told me. The AF brothers relied on these guys and when they were gone, the organization fell apart. Soon Ramon Arellano Felix was dead and Benjamin was in prison, where he remains today.

So, we’ll see.

We’ll see, too, whether this has any effect on the flow of drugs into the United States from Mexico, though I suspect not so much.

Meanwhile, the corrido factories ought to be working overtime as we speak.

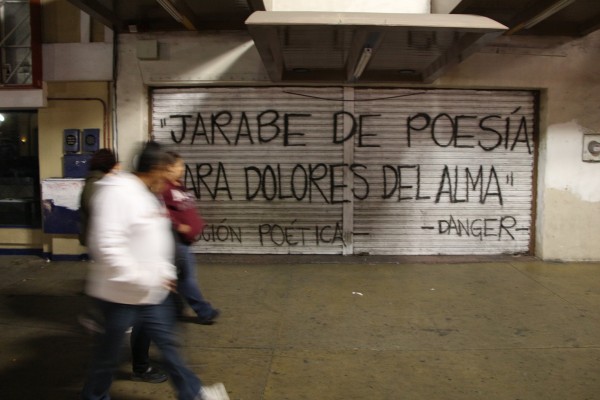

In fact, Guzman’s power and the barbarism of the drug war he unleashed when he made that fateful move across Mexico to the Gulf states, changed forever the nature of the traditional corrido. It was once a brave genre of music, extolling lonely, heroic men, outgunned and doomed, who nobly faced off against power. Now the corrido is about praising the virtues of colossally rich, well-armed and bloodthirsty men whose power is beyond question. Ads, basically.

Chapo Guzman was a major subject of corridos (ballads) and he appeared to have an army of youtube.com producers churning out videos lauding his achievements.

Here are a few Guzman corridos from the past:

http://youtu.be/Tx6N5AHpoqQ

and

http://youtu.be/FXPfkGv7feM

Photos: Most Wanted poster; Time Magazine cover, Wikipedia map of Sinaloa Plaza bosses.

Other Reporter’s Blog posts:

Last Arellano-Felix brother killed at birthday by clown.

Manuel Torres — El M1 – killed

Writing workshop in Stockton

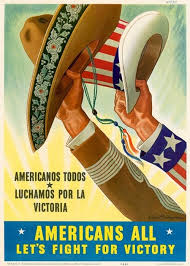

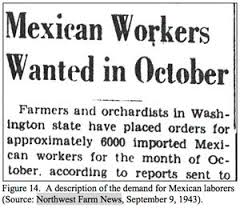

This month marks the signing of the Bracero Treaty between the U.S. and Mexico.

This month marks the signing of the Bracero Treaty between the U.S. and Mexico. Michoacan and others – and has become a business for many.

Michoacan and others – and has become a business for many.

I’m watching Greece vs. Costa Rica and Greek tragedy is on display. Replays have shown at least three pathetic pieces of Greek faking.

I’m watching Greece vs. Costa Rica and Greek tragedy is on display. Replays have shown at least three pathetic pieces of Greek faking.