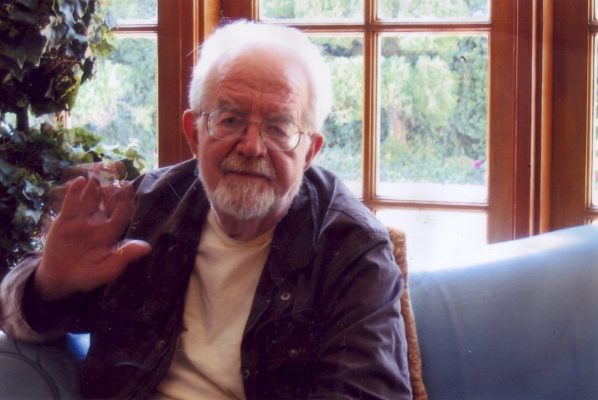

My dad died early Friday morning. He was a great father, loved his boys fiercely, a beloved and tempestuous literature professor at Claremont McKenna College, a husband, scholar and author.

I’m only beginning to understand how much I’ll miss him.

Here’s my obituary for him, which I’ve submitted to the newspaper in our hometown:

_________________

Ricardo J. Quinones, a long-time Claremont resident and retired comparative literature professor at Claremont McKenna College, has died from complications of a many-year struggle with Parkinson’s Disease.

Prof. Quinones was also founding director of the Gould Center for Humanistic Studies at the college, which now has a distinguished lectureship in his name. For several years, he served on the board of directors of the National Council for the Humanities, appointed in 2004 by President George W. Bush.

He died in hospice care at his home in West Los Angeles on Jan. 25, 2019. He was 83.

Prof. Quinones and his young family arrived in Claremont in an old Buick station wagon in 1963, straight out of Harvard University, where he earned his PhD under renowned literary scholar Harry Levin.

Over the years he became a fixture on the small, growing campus, a beloved teacher for generations of students, in love with his subject. He was chosen Professor of the Year in the mid-1970s. He was also at times a tempestuous figure. He protested the Vietnam War, supported the Civil Rights Movement, loved Robert F. Kennedy and voted for George McGovern.

Years later, with increasing encounters with a stifling political correctness in academia, his politics veered away from the Democratic Party, believing it had left him, though his favorite presidents remained Harry Truman and John Kennedy.

He was one of the first presidents of the Association of Literary Scholars, Critics, and Writers – which formed in 1994 in opposition to the politicization of debate in the humanities and as an alternative to the Modern Language Association, the mainstream organization of literature scholars.

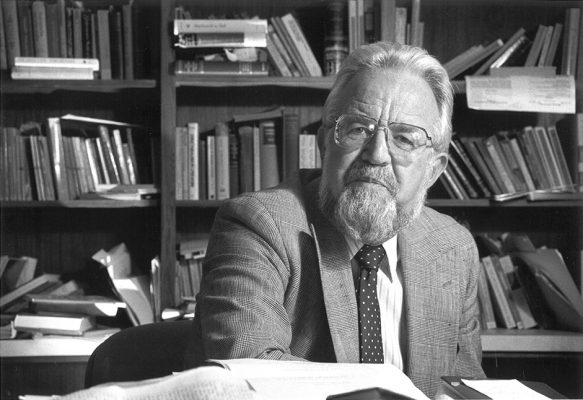

Through it all, he loved reading and literature and all kinds of stories, baseball and basketball, movies, especially gangster movies, and The Godfatherabove all. He was as delighted by Bird and Magic as he was by T.S. Eliot and King Lear. During the 1963 move to Claremont, he entertained his then-two young sons with the stories of Odysseus, and his office was a famous chaos of books and papers piled in seemingly incoherent stacks, in a filing system only he could decipher.

In his long career, he wrote nine books of literary criticism, including three in retirement while battling Parkinson’s. He was a noted scholar and expert on the works of Shakespeare, Dante, and James Joyce. He was selected to write the entry on Dante Alighieri for Encyclopedia Britannica.

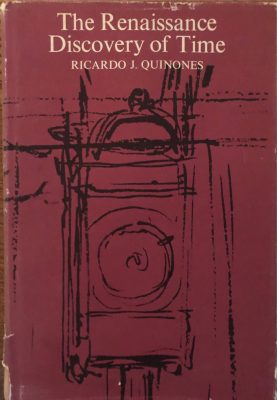

His last book, North/South: The Great European Divide, in 2016, was a discussion of Protestant and Catholic Christianity and their effect on economic development. His first book,The Renaissance Discovery of Time(1972), is considered a standard of literary studies of the period.

Novelist Charles Johnson used Quinones’ book, The Changes of Cain, an exposition on the Cain-Abel theme in literature, to influence his 1998 historical novel, Dreamer, about the life of Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.

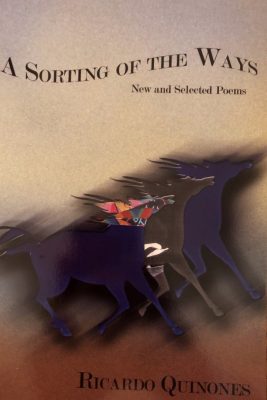

In retirement, he also wrote five books of poetry. His poetry tended toward storytelling. He wrote a poem about the plane that went down in that Pennsylvania field on September 11 – Shanksville– and another about his memories at age 10 of the men returning from World War II.

As the disease withered his muscles and twisted his fingers and toes, he nevertheless held poetry events, with actors reading his work, combined with a cellist or a violinist.

Ricardo Quinones grew up in Allentown, PA, the second child of Laureano and Maria Elena Quinones: He an immigrant from Galicia, Spain and a worker in a brewery; she a worker in a sewing factory, born in America to a large family of immigrants from Calabria, Italy.

Laureano Quinones had been born an illegitimate child, abandoned by his mother in his seacoast village in Spain. Leaving her baby with relatives, Eliana Otero fled to Argentina and was never heard from again. Laureano was raised by an uncle, taking the uncle’s last name of Quinones. At 20, he left Spain and, alone, made his way to Puerto Rico, where he cut sugar cane, then to New York and finally to Allentown, PA, where he met and married Maria Elena Matriciano.

They lived in the First Ward, a teeming, densely packed neighborhood of immigrants from Italy, Poland, Hungary, and Syria, who had large families and came to the town for its easily available manufacturing jobs. Bethlehem Steel and Mack Trucks were among the mainstays of the town.

Growing up, Ricardo Quinones was an altar boy and a copy boy at the Allentown Morning Call newspaper, where he one night shepherded the news that Hank Williams had died.

A friendly priest channeled him into college, something rare for kids from the First Ward, where many parents had little education and spoke English poorly.

Like his father before him, he left the comfortable enclave and struck out into the world – taking a bus alone to Chicago and Northwestern University, a private school where upon his arrival he was the among the poorest students on campus.

Originally intending to be a journalist, he fell under the mentorship of Donald Torchiana, a Northwestern literature professor, and from there his career focus shifted to academia.

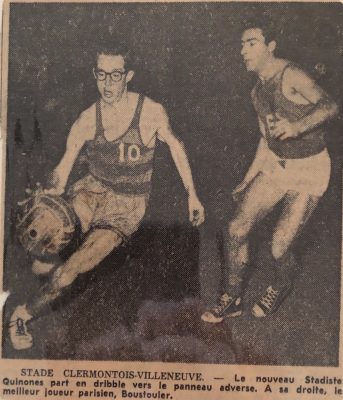

At Northwestern, he also met his first love, Lolly Brown, a student from an upper-class family in Des Moines, Iowa. They were married in 1956. Their early days were spent in Europe on a Fulbright Scholarship, studying in Italy, Germany, and France, where he played basketball for a club in the town of Clermont-Ferrand.

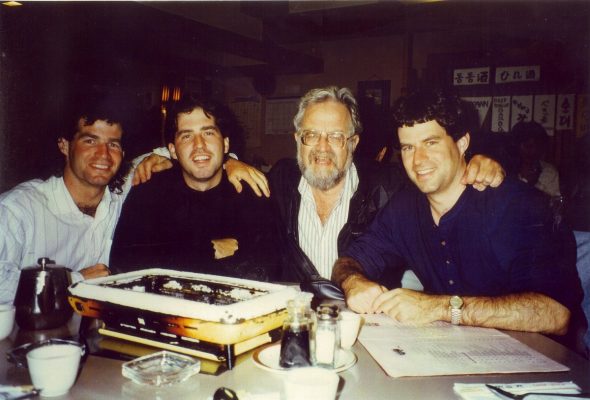

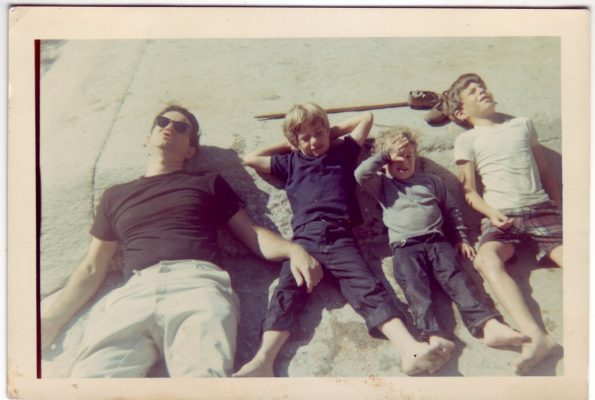

He came to Claremont as the town was morphing into a place of great musical, and artistic effervescence. His friends were poets and artists, then later political scientists and economists. His sons attended Oakmont Elementary, El Roble Junior High, and Claremont High School, and he sent them to Berkeley, Yale, and CMC.

He encountered death too young. His mother died when he was 11; his father when he was 22. His second son, Nathanael, died at 18 in a car accident in February, 1979, followed by his wife, who died of cancer that May.

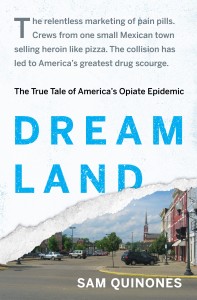

After that, he raised his two youngest sons – Ben and Josh – alone. They went on to become attorneys. His oldest son, Sam, is a journalist and author.

In the late 1990s, he met Roberta Johnson, a literature professor at Kansas University specializing in Spanish women writers. They fell in love and married in 1998. One of his books of poetry is titled Roberta. She cared for him through his illness, along with his wonderful caregivers, Anthony, Marlon and Ferdie.

In 2008, he survived the rupture of an aortic aneurysm, something few have done. Then, in a kind of slow-motion torture over many years, Parkinson’s took most of what made the man. He could only shuffle toward the end. Yet he wrote every day, pecking away through each morning, until the very end, when it took that from him, too.

Apart from cigars, Italian food and red wine, books were the only material possessions he loved. At his home, his shelves remain the earthly expression of his fertile mind. In his stacks is Heaven: A History, and The History of Hell. One of his favorite poets, the storyteller Robert Frost, stands in between Joe Stalin and Martin Luther; Henry Kissinger’s World Order next to Lord of the Flies — testament to how he enjoyed throwing ideas together and seeing what the collision produced.

On Christmas Eve, when his sons’ families were about to meet for dinner, they thought it best he not come over but instead head to a hospital for his low blood pressure. It didn’t seem safe. But he insisted on being at the dinner. Demanded it. Marlon Batiller, his dearest caretaker, told him, if you can stand, I’ll take you. He stood. On this, his last family Christmas dinner, more fragile than ever, he read For the Union Dead by poet Robert Lowell.

A few weeks later, on his last time out of bed, he asked Marlon to pull him up and into his wheelchair, and roll him into the dining room. There, on the table, sat the readings for his next project. It was to be a book about the 1800s, though he wasn’t sure yet what. His reading for it included Treasure Island, Huckleberry Finn, biographies of U.S. Grant, Napoleon, and others.

He’d grown to love Grant. He added him to his list of favorite presidents and defended him vigorously as mistreated by history.

That morning, emaciated, he sat in his wheelchair beside his books. He held the Grant biography. Then he leafed through the Napoleon. The books were new, and thick, and heavy and he re-read a bit from each.

Finally, he placed them back on the table and he sat in the chair in silence just looking at them one last time. And after a great long while like that, he asked Marlon to wheel him down the hall and back to the bed, where, two days later, he died.

A public memorial service will be held Sunday, April 7 at 12:30pm at the CMC Athenaeum.