In Louisville the other day, I wanted to see how jail was changing in America.

This epidemic of opiate addictions calling on us to reexamine a lot about how we live, our values, culture, ideas and institutions we’ve taken for granted.

One of them is jail. Jail has always been a crippling liability in our fight against drug abuse. Jails are usually places where humans vegetate, sit around, argue, learn better criminal techniques, then get out weary and stressed and, if they’re addicted to drugs, they head straight to the dealer’s house.

This epidemic is forcing new ideas. One of them is jail turned into an asset, a place of nurturing, of communion as addicts learn to help each other.

That’s a bizarre concept. I never thought I’d write “nurturing” and “jail” in the same sentence, but it’s happening.

The state of Kentucky seems furthest along in all this. I wrote an Op-Ed column for the NY Times about a visit I paid to the jail in Kenton County, Kentucky. Yet what’s being tried in Kenton County – and a couple dozen other county jails in Kentucky — began in Louisville – in Metro Jail.

Why jail?

Well, if “we can’t arrest our way out of this,” as is so often said, then we need more drug-addiction treatment. Yet this epidemic has swamped our treatment-center infrastructure. New centers are costly to  build, politically difficult to site, and entering them is beyond the means of most uninsured street addicts, anyway.

build, politically difficult to site, and entering them is beyond the means of most uninsured street addicts, anyway.

I know that jailing addicts is anathema to treatment advocates. But opiates are mind-controlling beasts. Waiting for an addict to reach rock bottom and make a rational choice to seek treatment sounds nice in theory. But it ignores the nature of the drugs in question, while also assuming a private treatment bed is miraculously available at the moment the street addict is willing to occupy it. With opiates rock bottom is often death.

Jail can be a necessary, maybe the only, lever with which to encourage or force an addict to seek treatment before it’s too late. In jail, addicts first interface with the criminal-justice system, long before they commit crimes that warrant a prison sentence. Once detoxed of the dope that has controlled their decisions, jail is where addicts more clearly behold the wreckage of their lives. The problem has been that it’s at this very moment of contrition when they have been plunged into a jail world of extortion, violence, and tedium. It’s a horrible waste of an opportunity, and almost guarantees recidivism.

With this epidemic, though, we’re seeing new approaches – jail as a place of rehabilitation, a place where recovery can begin.

Several years ago, as heroin began to grip the area, the Louisville jail saw inmates dying from overdoses.

Mark Bolton, the jail’s director, said the spate of deaths forced new ideas.

“We modeled a pod on outside treatment (centers),” he said. “It became a matter of taking the resources we had and repurposing them. We sent people [to drug rehabilitation centers on the outside] and found out how they run their peer detox program. We learned from them.”

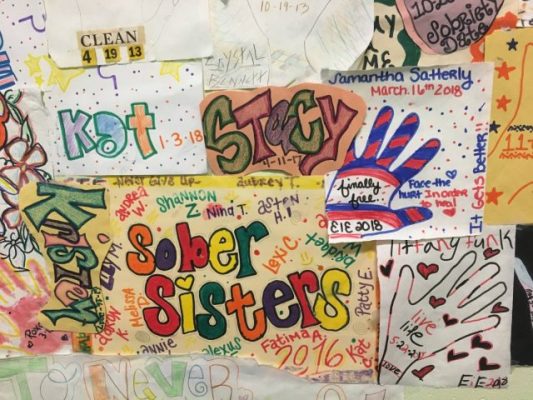

Louisville Metro began with female inmates. Those who were just off the street and detoxing, and who normally were spread across the jail, were placed together in one pod, christened Enough is Enough. This allowed more focus on their needs, and got them away from other inmates who were angered by their withdrawal symptoms, which included vomiting, diarrhea, screaming, insomnia and more.

Jail officials began allowing people in recovery into the detox pod as well. These recovering addicts mentored the new arrivals – washing and soothing them. Officers preferred it, as they no longer had to clean up vomit and diarrhea.

In addition to bathing and caring for those in withdrawal, inmates take classes in relapse prevention, understanding criminal thinking, accountability, parenting, and more; they run their own 12-step groups.

As the Enough is Enough pod began to function, there were fewer fights, less contraband. “Inmates into their recovery and into their sobriety are self-policing. The wear and tear is less,” Bolton said. “After we worked out the bugs, we began to see some of these people show progress. The inmates into their treatment appreciated the fact that they were caring for a human being that was at a place where they had been once.”

When they leave jail, they’re given a Vivitrol shot, which blocks opiates, and they were connected with housing and follow-up Vivitrol shots.

The jail now has the one women’s pod and three pods for men: 56 detox beds and 64 recovery beds, total.

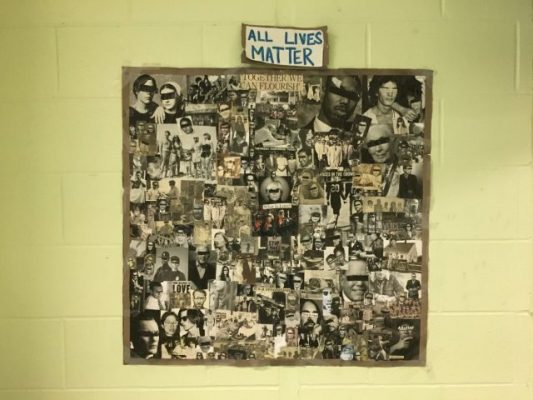

I visited the pod – with about 30 women, four of whom were detoxing. The walls were covered with art work.

(Click here to hear the end of the pod’s afternoon meeting that day.)

It seemed, finally, a nurturing place in jail – far more about recovery than its connecting pod, where fights and loud noise were common until the early morning.

I spoke at length with a woman named Kara, whose addiction was more than 20 years old. This was her 17th time in jail. She had come from washing the vomit off another woman who had just arrived in the pod.

Here’s our interview:

The Louisville jail experiment isn’t a cure-all – no one thing is for this opiate-addiction epidemic. And the jail has difficulty tracking inmates who leave, so it’s unclear how well they do on the outside. What’s more, inmates by this time face a daunting uphill trudge to sobriety, hampered by family dysfunction on the outside, shredded personal relationships, a private sector wary of hiring them, and on and on.

And of course, there isn’t nearly enough in available treatment options.

“I would love to shut some of these programs down,” Bolton said. “This shouldn’t be the jail’s responsibility. [Addiction] is a public health issue. Our job is detention, protection of the public, to get people to court. When we have to become the quasi mental health facility for people who are poor and don’t have access to services, or for people who are drug addicts and who’ve created these chaotic lifestyles for themselves and can’t get treatment in the community — then we become this de facto fallback place for everybody. That’s not what jails are designed to do, nor should they be.”

Yet until a massive investment in community drug rehab and medically assisted treatment takes place, it’s likely that pods like Enough is Enough will be necessary.

It also occurs to me that with jail rethought and remade — a nurturing place — we have the chance that it will be an asset in the next drug scourge that comes along.

Either way, as with Kenton County, it seems like a better bet of public money than the way jail has been done up to now.

This comes from interviews with many recovering addicts whose lives were saved by being arrested, by going to jail and facing prison time.

This comes from interviews with many recovering addicts whose lives were saved by being arrested, by going to jail and facing prison time.