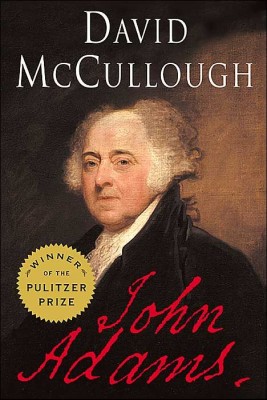

I just finished David McCullough’s terrific biography of John Adams.

John Adams was a simple man. He loved the same woman all his life. He never owned a slave. In his youth, even as an ardent revolutionary, he defended British soldiers in a trial because he believed everyone deserves a fair hearing in court.

He proposed complete religious freedom because he held firm to the Protestant view that every man is equal before God. He endured years-long separation from his family living in Europe doing the country’s difficult and crucial foreign business in England, France and the Netherlands. He despised the luxury he saw in Europe, and believed it would lead to corruption.

He believed strongly in the balance of powers. He lived his last years as a farmer, still earning a living, living a simple life. He also read and wrote voluminously.

I have been developing a considerably dimmer view of Thomas Jefferson, Adams’ vice president and successor to the White House, that this book did nothing to change.

Jefferson wrote the Declaration of Independence, and promoted religious freedom, and established the University of Virginia. But he owned dozens of slaves, fathered children with one of them and freed only five of them upon his death – the mother of his children was not among them.

He lived the life not of a simple American farmer, as Adams did before and after his presidency, but of a European aristocrat – expanding then tearing down Monticello several times, all of which depended on revenue generated by the labor of his slaves. Adams died solvent; Jefferson, despite owning slaves, died $100,000 in debt.

Perhaps slave ownership allowed Jefferson the luxury of his utopian vision of a country of small farmers and an equally small government. He never apparently asked himself the hard questions of how those small farmers might get their goods to market without government taxation that allowed for the building of roads and bridges, and law enforcement to keep the goods safe. This vision sadly left him equally enamored of the French Revolution, even after that event descended into wanton murder. These victims he viewed as casualties of war, and, from this grew his famous statement that “the tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants.”

Adams was the deeper thinker and had a more mature understanding of self-government. He understood that for a union to work, taxes had to be paid, and a national government thus allowed to function. Anarchy would result otherwise. It seems to me this is an idea one segment of our country doesn’t, or doesn’t want to, understand.

Adams began the U.S. Navy, and thus kept us from war with France when we were too small and weak. To do this he imposed taxes that earned him Jefferson’s ire, his own defeat, but the country’s lasting gratitude.

Adams also rightly feared the horrible cost slavery would exact on the country, and abhorred its expansion following the Louisiana Purchase.

Both men, however, embodied the key to the success of the American Revolution, for both were lawyers. Despite its numerous contradictions, slavery being the main one, the American Revolution was made by lawyers, and thus the rule of law not of men was its cornerstone. The tenets of self-government they had thought out and debated in some detail. This is why the Revolution did not collapse into slaughter.

Having lived in a country where the rule of law is weak, I can say that this is fundamental. There is no justice, no equity, no development, no innovation without the rule of law. To the fact that the Founding Fathers were, for the most part, lawyers, and many of them thoughtful about the biggest questions, we can attribute the Revolution’s success.

Interestingly, it might easily not have been so had the wrong people gained power – Alexander Hamilton for one, I suspect. We’re enormously lucky that our first president was, though a general, so unwilling, and left power as quickly as he could.

At the end of their lives, Adams and Jefferson, friends, then adversaries, were friends again.

In one of the great details in U.S. history, the last two signers of the Declarations of Independence died within hours of each other on, amazingly, July 4.