Four years ago today, April 15, Dreamland was released after a lot of work, interviews, travel, and endless revisions.

At the time, my family and I thought the book would fail and fade quickly because throughout my research I found people – families mostly – very reluctant to talk. This issue remained largely hidden, though I judged it to be the country’s worst drug scourge.

But those families were ashamed, mortified that loved ones were addicted, and thus they kept silent.

In the four years since Dreamland came out, I’ve been thrilled to watch awareness of the problem spread, and the response to the book grow every year more intense.

Media outlets now devote large pieces to it.

Families now speak publicly about it, instead of staying in the shadows. Their obituaries are more likely nowadays to tell the truth. That’s healthy for those families, and for the country.

Politicians have expanded budgets and enacted new policies to fight this problem.

Opiate addiction is now recognized as one of the top issues facing the country, which is where it should always have been.

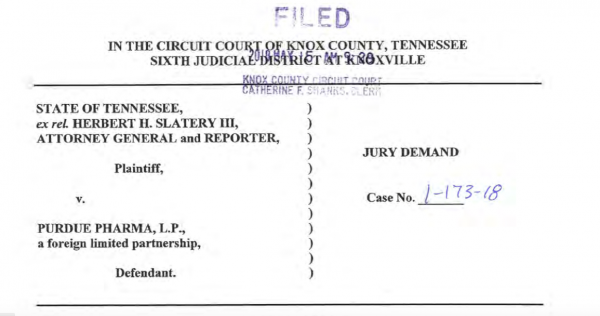

When I was writing Dreamland, there were three lawsuits against drug companies. Today, there are some two thousand plaintiffs: counties, towns, Native tribes, Attorneys General, and more.

So I wanted to take a moment to thank all of you who have read Dreamland, who’ve passed it around, read it for book groups or in classes, gave it as gifts, pestered co-workers to read it, and talked about it endlessly.

Thanks, too, to elected officials who have used it to shape policy, doctors who’ve used the book to inform their practices, families who’ve gone public, and podcasters for sharing it.

As I’ve spoken all over this country — more than 200 times since the book came out — I’ve realized how important word-of-mouth has been.

I have cherished the chance to speak to so many kinds of groups: public health nurses, judges, drug counselors, coroners, librarians, doctors, legislators. And more.

I’ve especially loved the chance to visit small towns where I assume authors don’t often show up: Tiffin, Bluffton, Leadville, Hendersonville, Whitewater, Whitehall, Marion, Peoria, Van Wert, Springfield, Newark, York, Worchester, Jeffersonville, Chico, Morehead, Mishiwaka, Spartanburg, Simi Valley, Greensboro, Scottsburg, Chillicothe, Grosse Pointe, Ashtabula, Marysville, and others.

I want to thank all the folks who helped me with the book when they didn’t have a clue who I was. Especially the good people of Portsmouth, Ohio, where I kept on showing up to listen to stories of pill mills, of a beloved swimming pool, and finally, of recovery.

There’s still a long way to go in all this.

The numbers of deaths remain staggeringly high. Each one reflects crushed families and friends. I think a lot about them as I’m on the road. I meet them everywhere, though I often don’t know what to say, or whether what I say is of any help. So I tend to do a lot of hugging.

One crucial issue is convincing insurance companies to reimburse for pain treatment that does not involve opioid painkillers. This would allow doctors to fashion a more holistic array of treatment for chronic-pain patients, instead of just cutting them off from the pills and forcing them, cruelly, into the black market.

A Young Adult version of Dreamland will come out this summer, which I hope will allow high school teachers to guide students in understanding, discussing, and, who knows, taking action in their communities.

I’m working now on a follow up to Dreamland, which will chart the epidemic and all that’s happened surrounding it in the last several years.

All that is to come.

For now, I’m shaking my head at the long amazing trip that Dreamland has been so far, and my family and I thank all of you who read it for allowing the book to play a role in our national story and yours.