This month marks the signing of the Bracero Treaty between the U.S. and Mexico.

This month marks the signing of the Bracero Treaty between the U.S. and Mexico.

The 72nd anniversary – not a sexy number, I guess. But the moment seems relevant given the crisis of unaccompanied kids flowing up from Central America, in especially large numbers over the last couple months.

The furor, the appearance of the kids themselves, are part of the complicated perversity that now surrounds the immigration issue, where Americans want and don’t want immigrant laborers. It all began with the Bracero Treaty.

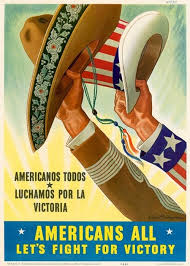

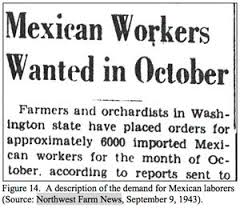

The treaty was signed in 1942, allowing Mexican guest workers to be contracted to work the fields of the United States, harvesting the food that the country and its military needed while men were fighting World War II.

Mexican laborers from isolated villages were contracted to work in Utah, Arkansas, Washington, Nebraska and, of course, much of California. There’s a lot that accompanies the story. (Here’s a preview to a documentary. There’s an historical archive here.)

But the important thing here is that the treaty began the transformation of America in many ways. First, it began the transition of agriculture, particularly in California, away from white, native-born labor to eventually an entirely Mexican, and then Mexican Indian, labor force today.

(In the early 1960s, Cesar Chavez, just then organizing farmworkers, was a main opponent of the treaty, and lobbied hard to end it. He was equally a fierce opponent of illegal Mexican labor.)

Our desire for cheap, plentiful labor trumped our dedication to the rule of law – a recurring theme through the next decades. So, crucially, the first large flows of illegal immigrants came at the same time as the two million legal laborers contracted under the treaty over its 22 years.

That, in turn, began the custom of migrating illegally that took hold in many Mexican states – Jalisco, Zacatecas,  Michoacan and others – and has become a business for many.

Michoacan and others – and has become a business for many.

Eventually, years after the treaty finally ended in 1964, its legacy would continue as construction and home improvement, meatpacking, gardening and landscaping, and many more, grew to depend on Latino immigrant labor. (Here’s a story I did on a gardener from Durango who died trimming a palm tree in L.A.)

The Bracero Treaty also began turning many parts of Mexico (and later Central America) into dependents of the U.S. economy. The first channels of immigration from certain villages to towns in the U.S. began with the treaty. That continues today. Some Mexican towns eventually just emptied almost entirely, a collection now of large, beautiful, unused houses built with immigrant dollars.

For a couple great stories about braceros, check out Tell Your True Tale: East Los Angeles, a book of stories from writers from East LA. Two of them are about braceros.

Here’s a link to one of them on my Tell Your True Tale storytelling website: Cardboard Box Dreams by Celia Viramontes.