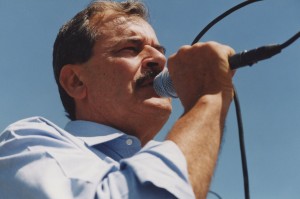

Alfredo del Mazo, of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), appears to have been elected Sunday as governor of the massive state of Mexico.

The state of Mexico surrounds Mexico City like a horseshoe. It is economically bustling and contains most of what is Metro Mexico City, with several suburbs with populations of more than 1 million people. It is the most populous state in the country (pop. 16 million).

For decades, it has been run by the PRI – which also ran the country as a one-party state.

(NB: For a good analysis, in Spanish, of why Del Mazo won and the effect this might have on the country’s presidential election next year, read this by Federico Berrueto, which ran after I published this blogpost.)

More than that, though, the state has often been run by a group of Priistas from one small town: Atlacomulco, a town (pop. 77,000) that has produced governors like Xalisco, Nayarit has produced heroin traffickers.

Del Mazo is not technically from this town, but his father was, and so was his grandfather. Both men were governors of the state of Mexico. Both men were PRI leaders. Del Mazo himself is a distant cousin to current Mexican president, Enrique Peña Nieto, who also hails from Atlacomulco and was once the governor of the state of Mexico.

Moreover, no group more exquisitely represents the worst of Mexican corruption than the governors from the town of Atlacomulco.

What’s popularly known as the Atlacomulco Group formed around an ideologue named Isidro Fabela in the 1940s and 1950s. The group shaped a governing philosophy that combined unregulated/crony capitalism with authoritarian, corrupt politics. Since World War II, of the 16 governors to run the state, seven have hailed from Atlacomulco. Others have taken their cues in how to govern from those from Atlacomulco.

(Each Mexican governor serves a six-year term, though during the PRI monopoly they often left office earlier to serve in the federal government or they finished the term of a governor who left early. This was particularly true of the state of Mexico, which has been a crucible for the formation of PRI leaders and high functionaries in the Mexican government during the years of the party’s political monopoly.)

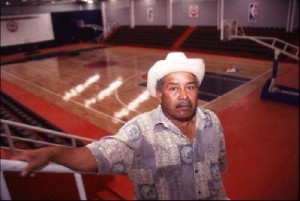

Carlos Hank Gonzalez, also from this town and also once a governor of the state and a protégé of Fabela’s, encapsulated this philosophy with a now-famous statement, which as decades passed was adopted by many PRI politicians:

“Un politico pobre,” Hank said, “es un pobre politico.” Translation: A poor (not wealthy) politician is a poor (bad) politician.

Atlacomulco governors ran the state like little chieftains, accumulating power and wealth and leaving behind dozens of public assets named for them. (In the map guidebook to metro Mexico City, the listings of streets, avenues, boulevards, parks, neighborhoods, etc etc named for Hank Gonzalez take up three pages.)

This kind of governor is now a standard in Mexico, as the PRI lost its national political monopoly in 2000 and the president lost his undisputed power. It is now in the governors’ offices where power is exercised, at least on a regional level. Instead of one king, there are 31. The results have been disastrous for respect for the rule of law in Mexico.

In 2012, Peña Nieto hailed a “new generation” of governors, ready to do the country’s business in a modern way. At the time, he listed four governors as examples – of which three are now facing criminal charges and are on the run. One of them, Roberto Borge, former governor of the state of Quintana Roo, was detained this week in Panama, on the run fleeing charges of money laundering.

A lot of that can be traced, I believe, to attitudes on governance forged in the state of Mexico by the Atlacomulco Group, and their power within the PRI over the last many decades.

I remember covering the town of Nezahualcoyotl – a slum town in the state of Mexico on the eastern edge of Mexico City (pop. 1-3 million people, depending on who you ask) after residents elected their first non-PRI mayor. The new guy found a city hall teeming with corruption and incompetence. Outside, I remember, were at least 12 newspapers that circulated only within three blocks of city hall. Each was only four or eight pages. They had no interest in reporting news. They were instead intended as organs of promotion for the career of one politician or another and used to attack rivals – all within the broad umbrella of the PRI. That had become a real job in Nezahualcoyotl and other cities in the state of Mexico: start a newspaper, find a politician to fund it and become his promotional vehicle. I still have a bunch of these newspapers somewhere in my files.

This is the legacy of the PRI in the state of Mexico and why I find the election of yet another member of the Atlacomulco Group, no matter how distant, to be reason for discouragement.

If there are clerics in this world due for a spiritual tongue-lashing, it’s Mexican bishops.

If there are clerics in this world due for a spiritual tongue-lashing, it’s Mexican bishops.

002 and 2003,

002 and 2003,