I’ve always wondered how novelists come up their books. Do they just start writing with a hunch and let the inspiration flow, taking them where it will? That seemed unlikely, given what I know about writing as a daily job, with inspiration playing only a minor role. (Or better put, inspiration flowing from consistent daily toil.)

Or, I wondered, do they spend days ahead of time blocking out their stories scene by scene? (Which is how my mind works.)

Each writer is different. Each follows a different path.

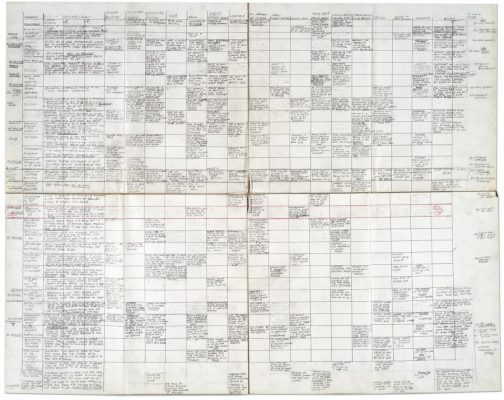

But I was cheered to see this outline that Joseph Heller came up with (presented in OpenCulture.com, a wonderful website, which I support financially).

It’s a chronology of events he describes in Catch-22 and it helped him keep track of the story he intended to tell in wildly non-chronological order.

(Full disclosure: I started to read the novel years ago and couldn’t finish it.)

I tried something like this with Dreamland – putting pieces of paper up on a mirror in my garage office, each representing a different chapter, which readers of the book will know are mostly 2-6 pages in length.

At one point my wife walked into the garage, saw this blizzard of paper taped to the mirror, and left thinking I’d lost my mind. But the papers helped visualize where the book was going and track the different storylines I was telling. It helped also when it came time to rearrange the order some of the chapters came in. I’d just untape a chapter and move it somewhere else on the mirror. At one point I had six rows, each with 5-7 chapters per row.

Apparently other writers find this visualizing necessary first before telling a story.

“Every great novel—or at least every finished novel—needs a plan.”

I think it’s true in nonfiction as well.

My friend and former colleague Andrew Harrell once told me about one of his cohorts in graduate school. Andy described how his friend completed his PhD in social psychology by drawing pictures and creating the equivalent of a storyboard before attempting to put words to paper.

I also follow Robert Reich’s post and tweets and I am impressed with th way that he uses a whiteboard to draw pictures to illustrate his ideas and organize his thoughts.

And one final random thought – MS PowerPoint is a very useful tool for creating outlines that combine text and images/grapics. Once screens are created, they can be shuffled around to represent changes in logical-sequential order.

OK, I’m going to jump in here like I know what I’m talking about. I’m only going to address fiction vs non-fiction.

Non-fiction is always organized first. I usually do either an outline or a mindmap, and keep working them till they “feel right.” I do research, and sometimes do the “put pieces on the wall” tactic too. Whatever works to make the thing both make sense and flow.

Fiction, on the other hand, follows one of two methods. (And if you read much of the literature on writing, you’ll find both of these, along with vehement arguments for and against each.)

There is the “plot it all out” school. They use lots of tools, they do bios of all their characters, they may outline the entire plot like a history book, and they can tell you on day 1 what is going to happen at the end of the book.

Then there is the “write to find out” school. Basically, they believe that you start writing, and your characters will appear and tell you what is supposed to happen next. They can no more tell you what is going to happen in the next chapter than they can tell you what is going to happen next week.

Both schools think the other is nuts.

For the longest piece of fiction I’ve written, I somewhat combined the two. I had a basic outline, because what I was writing was a case study accompanying a non-fiction book. I convinced them to let me write one long case study, with each chapter of the case study going with one chapter of the book. So, I knew ahead of time the basic problems the fictional characters would be dealing with.

BUT … the actual story was through-composed. I would work to get the opening scene and opening sentence of each chapter, and then work to find the second, and so on. There were times when the story was coming faster than I could type. There were others where I hit a dead end, and had to just stop. Usually, when I came back to it, the next step was there waiting, where it had not been there the night before.

And here is the wierdest thing, but I swear it is true. More than once I would type some dialogue, or describe some event, and I would stop and say to myself “where did THAT come from?” It was not something I had planned ahead of time; it just came out of wherever the story was coming from inside me. And more than once, that unplanned dialogue or event prepped something that happened many chapters later, and I said to myself “So THAT’S what that was about.”

Ultimately, what works is what matters. I don’t subscribe to either religion when it comes to writing fiction, because I’ve experienced both. But I can say that it is possible to write by just writing, and that sometimes your own characters surprise you. 🙂

Bruce – thanks for this very thoughtful reply. great stuff. I’ve tried the write to find out approach and it hasn’t worked for me too much. I’m in awe of people for whom that does work. Maybe it’s my nonfiction brain. Everyone has a different way.

Thanks so much for sharing Heller’s technique with us, and yours, too. My mind works much like yours. I think of writing a novel, but am not sure my newspaper-trained mind can take those big leaps of fancy and create the believable dialogue.

I used a similar organizational plan for Living at Lake Chapala–like yours, it has 75 very short chapters. I use a 3-ring binder with sections and then chapter dividers. Last week revised and freshened the binder for an immigration book –each chapter has 2 parts — an interview with a supporting fact-based article.

I suspect “Antonio and Delfino” gave you similar organizational problems. It was a reading list option for the immigration class I taught for Lake Chapala expats this year. But, we read that meaty section from Chapter 1 in class. It sums up so much of what I wanted them to “get” so beautifully.

Judy – so nice of you to comment, and to have assigned “Antonio’s Gun and Delfino’s Dream” With my first two books the problems came mostly in what order to present the stories – should the story about the Henry Ford of Velvet Painting go before or after the story on Tijuana opera? should the story on the patron saint of Narco traffickers run close to the story on the lynching in the small town? – these kinds of questions were a big deal. Though with Delfino’s trilogy of stories, the challenge was where to break them up, where to end each piece.