Los Angeles has seen gang violence plummet in the last decade.

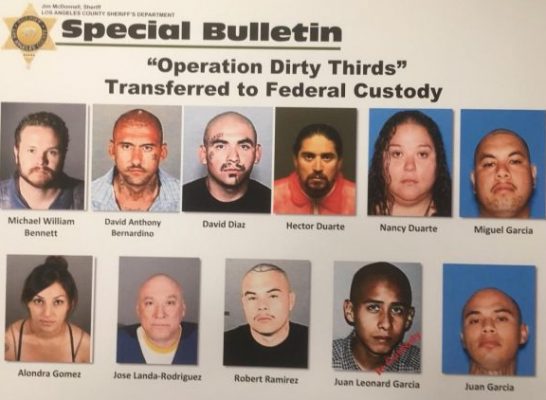

Some of the reasons why were on display in two federal criminal conspiracy cases announced this afternoon at a press conference at the L.A. office of the U.S. Attorney.

The cases involved the Mexican Mafia prison gang controlling drug taxation and trafficking in two places: The LA County Jail, largest jail in America, and in the city of Pomona.

The Mexican Mafia is a prison gang that runs the Latino gang members in the state’s prison system. About 25 years ago, it extended that power to the streets, ordering those gang members to tax neighborhood drug dealers and funnel the proceeds to MM members. Drug taxation thrives and amounts to the first regional organized crime system in the history of Southern California.

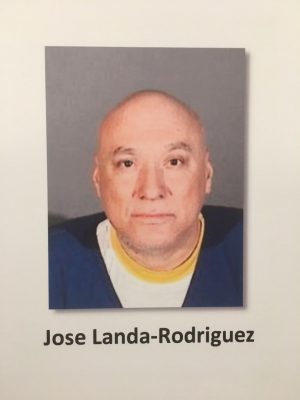

One case involved a Mafia member who controlled drug trafficking in the entire jail, according to the indictment: Jose Landa-Rodriguez, who grew up in East LA, a member of the South Los gang. He’s apparently been in county jail for many years, during the reign of the now deceased Lalo Martinez, a controversial MM member. Through those years, and after Martinez died, Landa-Rodriguez allegedly grew to control the drugs entering and for sale across the jail system.

Inmates not with the Mexican Mafia had to get his permission to sell. Only way to do that was by funneling a third of their product to the gang — hence the name of the case, Operation Dirty Thirds — then waiting while Mexican Mafia associates sold the stuff. That’s one way of controlling your competition. Violators were often beaten. That’s another.

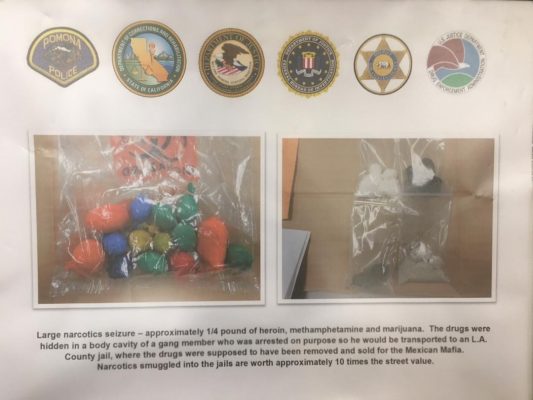

They were helped, prosecutors allege, by Gabriel Zendejas-Chavez, a local attorney whom investigators say helped facilitate the trade, passed notes back and forth between Mexican Mafia associates, and that kind of thing. They were also helped by a slew of go-betweens who would get arrested with drugs in their bodies.

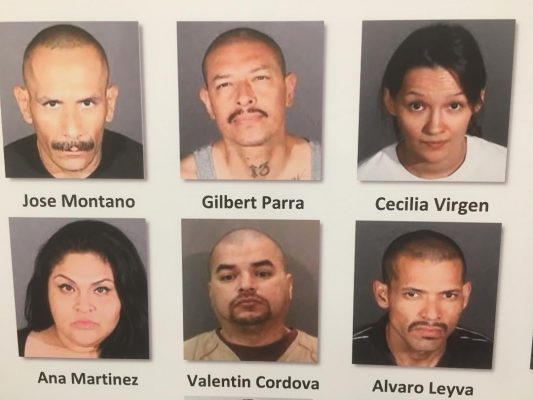

The other indictment involved a Mexican Mafia member named Mike Lerma, who has controlled Pomona for many years from his cell in solitary confinement at Pelican BayState Prison maximum lockdown. Crews of members from 12thStreet, Cherryville and Pomona Sur street gangs were working together under Lerma’s command, the indictment alleges. The indictment alleges Lerma’s crews did kidnappings, robberies, identity theft. These are Pomona gangs that have harbored animosity against each other for years, but have repressed the urge to go after one another due to orders from Lerma, according to officers I spoke with.

(Btw, I briefly met Mike Lerma one time, in his cell in Pelican Bay State Prison. We were separated by Plexiglass and he was cooking a cup of cocoa on his hotplate in his pale-yellow concrete cell where he spent 23 hours of every day. He was small, a wan and bent fellow, wearied by years on solitary confinement. From behind the glass, he waved, said how you doing? I said fine.)

The mafia’s system has forced gangs to abandon what made them local neighborhood scourges because it leads to unwanted police attention.

“Years ago, they were about turf,” said one. “Now they’re about protecting their business.”

For decades, they waged wars over turf. They defended street corners, parks, markets, apartment buildings like they actually belonged to them. They were very much street gangs, and their activity — graffiti, shootings, car jackings, simple hanging out through which they did their recruiting — blighted working-class neighborhoods across Southern California.

These days, though, they are absent. They have retreated into the shadows. Doesn’t mean they’re gone for good. Just that they’ve disappeared from the streets, no longer are out in public, damaging neighborhoods that can least afford it, spraying up mom-and-pop markets. Homicides are way down because gangs don’t have easy rival targets to shoot at. That’s one reason anyway. In Pomona, the once-notorious Sharkey Park – from which Pomona 12thStreet earned its name the Sharks (members often had shark tattoos) — hasn’t had a shooting in who knows how many years. Some Pomona cops at the press conference couldn’t remember the last one. As if to exorcise the past, the park has been renamed Tony Cerda Park, in honor of a Native-American activist and tribal leader; pow-wows are held at the park.

Gangs are just not evidence in Southern California. It’s a remarkable, profound change in culture and crime, and one that benefits cities, neighborhoods, and working-class residents most of all. Parks are once again places for kids to play. This is part due to dictates in the underworld, from organizations like the Mexican Mafia, who want their business protected.

But it’s also due to an unprecedented amount of collaboration among law enforcement. In the 1980s and 1990s, this didn’t exist. Agencies fought each other for credit, turf, budget, as the gangs grew fierce and brazen. But the last decade or more has seen a remarkable change and that too you could see at the press conference.

At the press conference, cops of all stripes assembled to thank each other for working together. The feds thanked the locals. The locals thanked each other and the feds.

“I want to give special thanks to our law enforcement partners,” said Pomona Police Chief Mike Olivieri.

(For the record, apart from Pomona PD, that includes the FBI’s San Gabriel Safe Streets Task Force, the LA County Sheriff’s Department, ATF, the DEA, Ontario Police Department, the IRS Criminal Division, the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s Homeland Security Division.)

“Today’s action is not an isolated event. Southern California law enforcement is united in its fight against violent criminals and street gangs,” said U.S. Attorney Nick Hanna, continuing the theme.

I’ve been to a dozen of these gang-conspiracy press conferences and I always like it when they thank each other. Because it wasn’t always that way.

Speaking with a prosecutor outside the press conference, we marveled at the change and wondered how the trauma of the 1980s and 1990s might have been avoided had this kind of collaboration been more common

Great point for pointing out on both sides of the ethnic thing. I know Big U from 60s had a lot to do with that. Should interview him instead of most reporters always reporting just from the Mafia side like the other don’t matter

Pingback: Pomona: Floodwaters & Blank Walls at (ex-)Sharkie Park -

I grew up in Compton through the 80’s and 90’s and too find the dramatic drop in gang violence fascinating. While your theory is plausible (both via control from La Eme and from police collaboration), it seems there are still doesn’t seem to fit the data as well as it should, if that was the primary reasons.

First, gang violence is down both with Mexican gangs AND Black gangs. In fact, even colors don’t get you killed anymore and an overall truce has seemed to hover over Black gangs too. Black gangs are also noticeably less visible in the very same areas as Mexican gangs.

Second, there are still hot pockets here and there, mostly in the outer areas of the LA area where it’s almost as if you were back in Compton in the 80’s – San Bernardino comes to mind. The Mexican mafia runs a tight ship: if it could control gang violence in Watts/Compton, it could certainly control it in San Bernardino…yet it can’t. Or is the law enforcement somehow rogue in these areas? I doubt it.

With that said, I am not sure I have the answer either. But it does seem like something deeper underlies all of this. My experience has been that the press, politicians, law enforcement and pundits are all too fast to credit large policies that really had little to nothing to do with the actual change on the ground. For example, the Mexican mafia in the 90’s dictating that Mexican gangs stop killing each other had alot more to do with the drop in murders than anything at the national level, or anything law enforcement did.

So what are my guesses? Ill throw a few out that I think are better explanations, though admittedly are not perfect.

One, culture. It seems like the hardest hit gang areas of the 80’s and 90’s are now the ones doing better, while the areas that escaped the gang highs of those years are now picking it up. Maybe seeing all their older brothers, dads, and even grandparents die or end up in prison had a tipping point? Also, it seems that somewhere around the early 2000’s, women stopped being interested in gangsters. When I was growing up, you almost had to be a gang member if you wanted to have any play in the dating scene – that all reversed, and women saw gangsters as rock bottom in terms of status. This alone had a HUGE impact on gangs. Why did this happen? It certainly wasn’t because of La Eme or law enforcement. Something bigger was happening.

Two, demographics. Alot of housing booms and busts changed demographics of certain areas. This spread the gang violence around. San Bernardino, for example, had a large influx of now “rich” ex-Compton residents that wanted to leave the ghetto. Maybe thats why San Bernardino is such a hot bed now?

Three, technology, my strongest argument. Everything you do now, is recorded. Everyone has cell phones. THe link between gang violence and prison time is ALOT stronger now. How many drive-bys (or walkbys, by La Eme rules) can a young gangster get away with now? Maybe a handful. When I was growing up in Compton, I knew people who have killed in the double digits, who had done probably close to 50 drive-bys in their lifetime (say, an active 20 yr old on his way out). This fits the data much better, as crime is way down all around and in all areas.

With that said, there are many things that add to the drop, at the edges. RICO laws definitely have an impact. Not being able to hangout in large groups takes alot of the fun (and appeal, and opportunity to do more violence, etc) out of gangbanging away. Law enforcement collaboration I’m sure had an impact, although likely a rounding number.

thanks for the thoughtful comment. really great points throughout. Fyi – some of this i talked about in a story a few years ago: https://psmag.com/social-justice/the-end-of-gangs-los-angeles-southern-california-epidemic-crime-95498.

Great point for pointing out on both sides of the ethnic thing. I know Big U from 60s had a lot to do with that. Should interview him instead of most reporters always reporting just from the Mafia side like the other don’t matter

Sam

Thanks for the post. You present a fascinating parrallel within the story that might be worth exploring at a theoretical level through an extended analysis. Which came first MM withdrawing or LE cooperating? Is there a clear cause and effect? Has MM “matured” as stretch violence is bad for business? Or is it RICO and other laws that allow organisations to be dealt with rather than individuals?

What is curious is no violence has entered the apparent street level vacuum of violence. Perhaps MM and LE in a sense “cooperate” in a perverse symbiosis to maintain the piece ie no third party can get access.

In any case, it is welcome news for those communities and people that had to live in the shadow of guns, violence, and death.